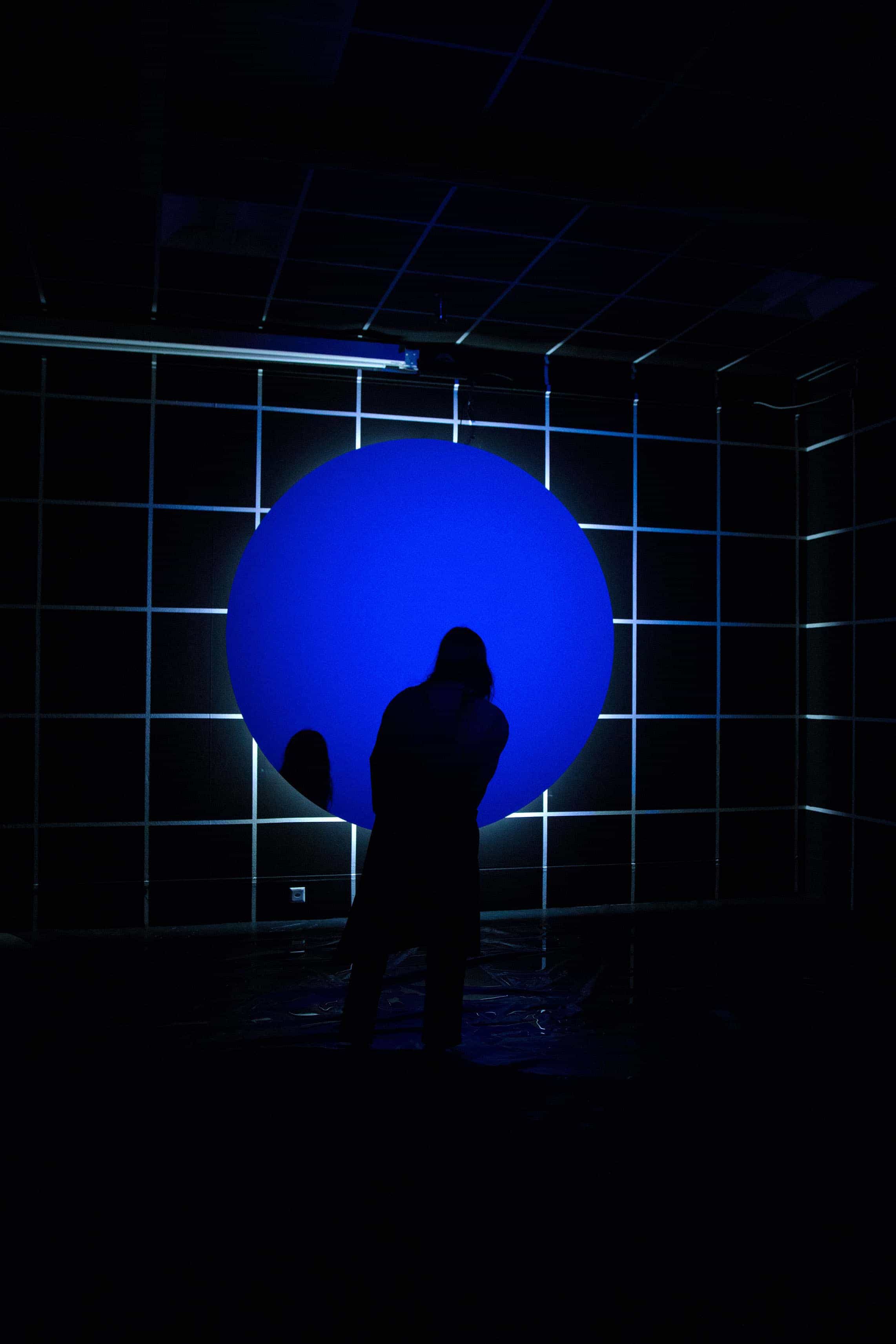

A club installation, followed by a presentation by Pol Esteve and Octave Perrault

24.05.2019 F’AR Lausanne

NIGHT CLUB belongs to a series of events from the project SCÈNES DE NUIT, that presents five nocturnal encounters exploring the role of night in the construction of contemporary cities and societies. The exhibition seeks to examine and reflect upon the spaces, activities and media unfolded in night culture, and uses evening events and ephemeral scenography as the main display platform. The scenography was developed by students of HEAD-Genève’s Bachelor in Interior Architecture

The Club epitomizes both the nocturnal public agora and a laboratory for technological and multimedia experimentation. Embedded in a one-night club where visitors are encouraged to explore and use the space, architects Pol Esteve and Octave Perrault reflect upon nightclubs as architectural types and upon the Cruising Pavilion at the 2020 Venice Biennale.

Curators: Javier F. Contreras, Youri Kravtchenko

Assistant: Manon Portera

Students: Taomei Bengone, Astrid Mayer, Deborah Marolf, Camille Nemethy, Julie Reeb, Annika Resin

HEAD–Genève Interior Architecture Department

Photos: © Jerlyn Heinzen

Presentation by Pol Esteve

Pol Esteve

First, I want to introduce myself and clarify what is my role and relationship with Octave who will be presenting later. I am Pol Esteve and I am an architect, a researcher, and a teacher. I teach in the Architectural Association and I do research at the Bartlett, both in London. I also have a studio in between London and Barcelona. I have been doing research on the topic of nightclubs and spaces for social dance after the second world war. I have done research in the past about spaces of cruising. That is why one of my pieces was exhibited, or rather part of my work, was exhibited in the cruising pavilion which was curated by Octave. I had the pleasure to present part of my work in the first edition of the cruising pavilion in Venice but what I will be presenting today has nothing to do with that. Hopefully, Octave will be talking about that later. Today I will be mainly talking about my research on spaces for social dance which is relating to the PHD thesis that I am currently working on at the Bartlett in London. I will explain first where the interest for these spaces came from, and how it became more of a methodological and disciplinary research to a certain extent, and how I am looking at the emergence of the discotheque. For this I will be using words such as discotheque, nightclub, or spaces for social dancing, but in any case, what I’m interested in looking at is the emergence of these spaces as a typological space in architecture. The interest for social dance spaces started when I was a student in Barcelona at the technical school of architecture 1

, which is a school who comes from the tradition of the polytechnic, and I was going out a lot in the city. I was being taught during the day how Mies and Le Corbusier are designing, which are fantastic guys but rather dry let’s say, and at night I was inhabiting spaces like Nitsa club, which is an important club in Barcelona that occupied a pre-existing theatre. And Torres de Avila, a very weird place, it’s a club that was inserted within a fake historical structure that was built for the exhibition about 1939 along with the pavilion for Barcelona by Mies. There was this reproduction of traditional pieces of Spanish architecture late in the nineties, Arrivas who was the architect, introduced this club inside of it. So, Barcelona at that moment, and particularly from the eighties on, but still in the 2000s when I started to go out was a place that was full of interesting night architecture. It was exciting and different, and it had different qualities than the architecture that was being taught at the university. And that is why I started to be interested in that. The interest was there for a while and when I moved to London I started to conduct research more rigorously, and one of the first questions I came across was: how can I talk about this, what am I talking about exactly, is the discotheque a rave? Is it a nightclub? What is it exactly that I am looking at? And how can I put all these things together. I had the intuition that all of these kind of spaces is a mixture of all the different spaces I was interested in, they had something in common but I didn't know exactly what was the common factor between a rave, for instance, and a club in New York from the seventies. There is something there, but it is not the same, the space is very different, the building is very different, the walls are different, the decoration is different, so what’s the relationship? I was trying to analyze the pictures themselves to understand what actually was there, what is the common thread between this rave for instance, and this club which is the Piper in Turino, one of the iconic clubs of the sixties. It was while looking through these pictures that I suddenly discovered some elements like the one that you can see here on the top, which is a piece by Bruno Munari, it’s a kind of small device that projects light and moving images on to the walls.

I started thinking, okay, what are these devices that appear in these spaces and what is their role in relationship to architecture. Then I found a text that was crucial for my research, which is a text by Roland Barthes, who is a French semiotician, who was sent by the magazine Vogue Home to the newest Paris night club in 1978, Le Palace. It was inside an existing theatre that was a theatre for varieties. All the text is fantastic, full of clever observations on how a discotheque actually works, but there was something for me that was very important from an architectural perspective, and it was this sentence: “The remarkable thing is not the technological prowess but the appearance of a new art in its material, a mobile light and in its practice”. He was saying that the discotheque was a new art, you can translate it to a new architecture, and the material is the light itself. And that kind of clicked something in me, these kinds of devices that I’m seeing in these spaces are the ones that are actually constructing the architecture, and the materials of these architectures are not the walls, that’s why the walls are different in every club, it doesn’t matter actually which walls and which decoration to a sort of extent, what constructs the experience of social dance space is the light. This picture from Hacienda, which is one of the most iconic clubs in Europe, from the eighties, also became quite revealing to me; because most of the time this club is shown from another point of view, from a lower perspective, and it’s mainly remembered for its application of colors to the columns, or particular materials that were chosen by Ben Kelly who was its designer etc. But when you look at the club from the top you suddenly realize that all this equipment that is above your head is the one that is activating the experience, and when you are inside dancing you don’t even see the color of the columns so to a certain extent its irrelevant.

Finally, what made me realize that I was going in the right direction was finding the first law that was mentioning nightclubs. To this date this is the oldest code that I have been able to find that directly describes in legal terms what a nightclub is, it was a code that was passed in 1979 in London by the Greater London Council. I really love the way they legally describe a discotheque, “for the purpose of this code, discos are defined as events characterized by loudly amplified music, dancing, flashing lights and mostly attracting people under the age of 30”,2

.The last part is a bit ridiculous; I don’t know what was happening at that time but obviously everyone can go to a discotheque, but definitely the other parts are there. For sure what defines a discotheque is not where it is, how big it is, or other parameters that might actually define a parking or some other architectural typologies and programs, here what defines it is, that there is pulsating light, changing lights, and that there is amplified music, which is the second element. I came to a conclusion that my research is on the technologies that allow for the experience of the discotheque, or the experience of the dance club to happen, there is light and sound for sure but there was something missing. Here I added, even if it was not in the code, there is a third technology that is extremely important, which is psychotropic technologies, or in other words, drugs. Normally these technologies are never regulated by the same laws that regulate the other technologies, normally it’s city councils, not even at the state level, that regulate light and sound, while drugs are normally regulated internationally. There are normally agreements like the Vienna agreement of 1973, in which they agreed upon which substances are legal and which are not, and obviously these substances, in coalescence with the light and the sound, are the ones that finally construct the experience of the club. So, the question at that moment was, okay the club is constructed by these technologies, but where do these technologies come from and who invented them and why were they invented. I’m going to go a bit fast because I realize that my presentation is very long, and it’s after 10pm so I will try to go a bit quicker. What I realized is that, as is the case with other technologies, most of technologies of the club, from the flash to the neon light to the laser, the laser being an exception, were all invented for a completely different purposes. They were invented mostly for dermatology, for investigating bodies in movement etc. and then later they were used, or translated, displaced for another use. Most of them were invented actually decades before the discotheque was put in place, it’s only after the second world war that there is a certain interest in revisiting these technologies and thinking how they could be used in a different way. This happened with light technologies, but also to a certain extent, it happened to sound technologies too- which were initially intended to record voices and then used to reproduce music. They were also used as weapons at a certain point, the lower frequencies that then became de subwoofers were used as a weapon to activate the bowel of the adversary so that they could not fight anymore. Many of the technologies that will occupy the discotheque later were tested either in laboratories or during war periods by the military, as is the case with drugs or the psychotropic technologies. Just recently some of the classified files of the American military came out revealing that MDMA had been tested extensively within the military to understand what consequences there would be if it were used as a chemical weapon. So, all these technologies originally had different purposes, at some point someone had to rethink what to do with them and that is what I wanted to discover. I thought my work to a certain extent was complimenting or continuing the work of Sigfried Giedion, which is an art and architecture historian that I really love, and he did this fantastic work which is Mechanization Takes Command ,3

. He was basically trying to trace the anonymous history of mechanization in inhabiting spaces, so how houses and public spaces, the factory etc. incorporated mechanization. What is interesting here is that Giedion traces a relationship, or a direct connection between mechanization and optimization of the movements of the body. He claims, and this diagram that we can see here by Gilbert is a study, of how a person in the factory can do the movements in more effective way so not to lose time and to be more productive. And the house was doing exactly the same, when you invent a compact kitchen it’s exactly the same, how can a women produce food by wasting less time and then have time do something else in the house as well, so she is actually in control of the full house herself. Behind this there was also the idea that mechanization was controlling the body and the performativity of the body and what happens later on when certain technologies change their roles and begins to work in a different way, is my hypothesis, and we will get to that later, it liberates the body, it re-eroticizes the body and gives it back the freedom it was losing through mechanization. Before these technologies came together as a discotheque, the first examples happened in laboratories, mainly in North America, UK and partly in Europe, they tried to put people under the effects of drugs in combination with the effects of flashing lights, and surprisingly what they discovered is that when you are under the effects of flashing lights or a stroboscope and it has a certain rhythm, the waves of your brain change.

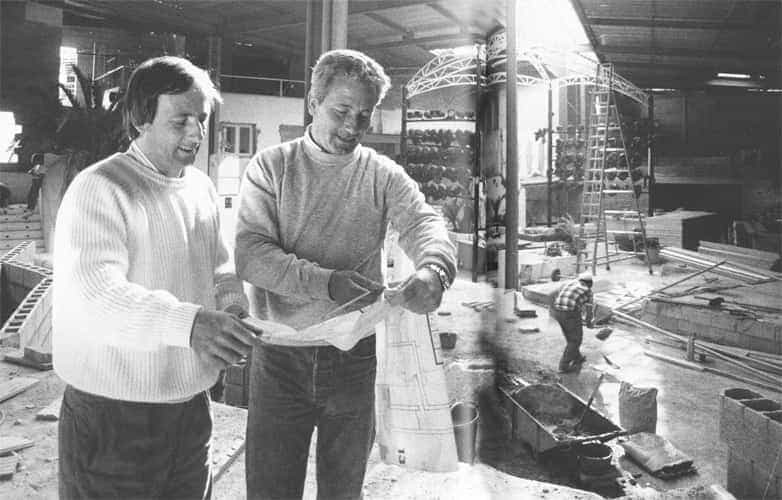

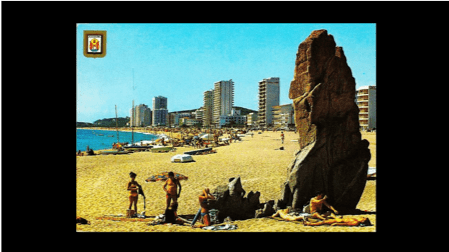

The alpha waves are the waves that activate your brain when you are not having purposeful thinking, so when you are closing your eyes for instance your alpha waves go higher, and this also happens when youre under the effects of a stroboscope, obviously if on top of that you are taking certain drugs this is multiplied by ten. So, there is a certain scientific explanation of what the experience of the discotheque is, as being this moment in which you can lose yourself, you can lose your subjectivity, you can go into the experience of jouissance. I focused on Europe because even if nobody agrees on where the first discotheque emerged, there is actually no official history of that, no book to check, there are many little histories around from blogs on the internet to people that know something, to little publications etc., and everyone claims something absolutely different, and it’s not so clear. For sure it happened in between the fifties and the sixties somewhere but there seems to be some form of agreement that it first started in Europe and then it moved to America, when disco as a musical genre started there in the late sixties and seventies. So, I decided to focus on Europe, and what is an iconic place in Europe to look for nightclubs, obviously it’s Ibiza. One of the most iconic nightclubs in Ibiza is Pacha, maybe you know it, if not I can tell you it was one of the first ones, and one of the most important ones, and Ricardo Urgell who is this guy there, who at that time was building the club in Ibiza, in one of his interviews,4 says, “yes I did this club in Ibiza but firstly I opened another club in Sitges actually. So, this one was opened in 1973 and the one in Sitges was in 1967 but even when I opened the club in Sitges I was inspired by the clubs in the most fantastic place which was Platja d’Aro.” And Platja d’Aro is this village in the north coast of Spain where most of the clubs, let’s say of the Mediterranean, were tested at the very beginning. I discovered that most of the clubs in the sixties and late fifties appeared around the Mediterranean coast and in a great relation to the phenomenon of tourism. There was actually the idea of having a space and a place where you could lose your body for a period of time, and also the fluctuation of money from the north of Europe, since workers from the more industrialized cities of the north of Europe would come to the south, particularly to the coast, and have the money to invest in going out, in having enjoyable experiences, and people would make of that a business. And most of the experiments with technology, which were not cheap, but rather quite expensive were taking place in this context. So I took the case study of Platja d’Aro, to understand a bit where it comes from, Platja d’Aro is the municipality and there is a beach called Sun d’Aro, and it was a master plan by the famous Catalan architect Masó to build this village in the twenties. Here is only an image of the main beach, part of the architecture is merged within the landscape, it was made for the aristocracy and the bourgeoisie, there was a huge emerging Catalan bourgeoisie, to go there on holiday. This became an international spot and, in the thirties, already you could find magazines published in four languages, you would have the director of the Herald Tribune, the director of Life magazine going there to spend their vacations. And there were obviously parties during the night. These magazines were portraying the parties, all these parties had orchestras, or concerts of classical music or more folkloric music, and they were mostly happening in open air. But then later there is the civil war, there is a break and after the civil war there is a dictatorship in Spain, and with this dictatorship, there is an interest in promoting tourism as a form of getting money, of making the country grow.

So, this is exactly the same beach 30 years later with all these developments and where the first discotheques started to happen, this is Platja d’Aro in the sixties. What I found is this, here we will go quite quickly through the evolution of the typology of clubs in Platja d’Aro. This is the first club I found that was registered as a club that had the license to play music electronically, they didn’t have an orchestra and did not have the specific license for that. So, in the registry of the city council you can find that they were given the license to have a turntable. It was placed within an existing farmer’s house, so actually the house, the typology is quite normal, the only thing they were asked was to block the stairs to the bedrooms so there could not be prostitution. They could have the electronic music there, fine, and that lasted for twenty years, it was refurbished later and became a normal club later but that was the starting point. By 59 already there were two clubs in Platja d’Aro, made in a more serious manner because they re-thought the typology of the space in order to convert them into a “boîte” or a discotheque, and they were using for the very first time, also in Spanish, “pista de baile” or dance floor. Before this, I could never find anyone writing “dance floor” on the plan but here for the first time the architects were actually writing “this is a dance floor”. So, these were the two of them and they were also published in Cuadernos de Arquitectura which is one of the most important magazines of architecture, let’s say, or it was in the context of that moment in this region. And to go quickly into that, what is interesting about these clubs is that there was two dance floors and that they had a complete and closed perimeter. They had no windows, they had no contact with the exterior, they were related with the motorway, and they had a parking. They worked as a one piece of this ecosystem of tourism that was constituted of apartments, hotels, beaches, etc. that people from many of the different villages could transit with the car. And at night they could go to these spots which were the nightclubs and have fun inside of them, disconnected to the exterior, that’s why you have no views of the beach, no relationship, expect for the vegetation that might be in the garden. This was the first nightclub that introduces not only stereophonic sound but also light in a very particular way. This club was the first one where the dance floor had light that would sparkle under it. The dance floor was made of glass and you could dance on top and this would illuminate you. Again, here there is no connection with the exterior, the plan is quite neat, there is this empty space in the middle, and for the first time also, which will become a normal thing of the typology, you could see rooms for the workers to sleep. The first discotheques normally had the people working for the discotheque living in house, this was kind of a normal thing for the first clubs that appeared there.

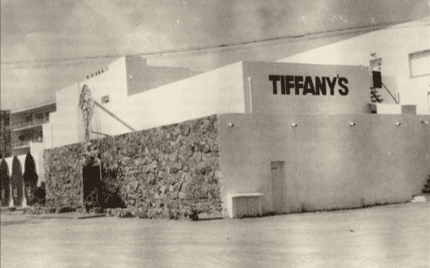

The first very famous club that actually appeared in Platja d’Aro was Tiffany’s, and as you can see from the exterior, it has nothing special, it’s just a white piece of architecture, it could be in Ibiza, it could be in Platja d’Aro, it doesn’t really matter, the important thing actually happens in the interior. This club was also developed next to the road, it was developed within two years, from around 64’ to 65’, the first part was this, a year later it was so successful that they added these other parts and the most interesting point is that actually the architect was pointing out in the architecture where the turntables have to be. This is the first time that I found a plan where an architect identifies the place of the DJ. In this club, this was the place of the DJ in 65. It was somewhat weird because it was a kind of fireplace, but the inside was full of this technology, so it’s like looking at a plan of Frank Lloyd Wright that would have the fireplace in the middle but instead what you have is this weird machinery that will activate the whole system. The guys that established this club were swiss, it was quite common that most of these clubs were done collaboratively, it was never one person behind them, it was normally a group of people. Before this club they had another small beach bar in the north of the coast, it was called San Trop and apparently there is where they tested a bit of these technologies. Then they decided, because their business was so successful, to invest in Platja d’Aro, it was the central touristic spot, so they constructed these clubs.

Here we have the first example of a built in DJ booth and that was not the only thing. What they tested, which was invented between the DJ and the owner, not even the designer, was all these ceilings full of stalactites that would have lights in them and would sparkle during the night. That was the main revolution of this club, and in the newspapers of the time when they were reporting about it, it was like- okay, you go there and there is this sparkling ceiling full of lights that blinds you, it was shocking at that moment to have this amount of technology put in place. After that came maybe one of the more representative clubs of Platja d’Aro which was Madox.

Behind it was a combination of a local entrepreneur, another entrepreneur from Barcelona, and an Italian architect that had studied in the polytechnic in Milan that moved to Venezuela then came back to Italy and ended up in Costa Brava, I don’t know how. He also called in a light designer that was coming from an experimental theatre in Italy and had worked in the Piper in Rome. So, it was a mixture of international people that came together to make this club. From the exterior its also quite a simple building, no windows, only one door to enter, and no connection at all to the outside thats completely insulated so you cannot hear the noise from the interior. The architect conceived this sculpture as an idea for the club, he said it actually needs to be a complete fluid space that allows the spirit of the new era to come play, something like that, he was a bit new age, at the moment it was already the late sixties, this is 67.

And he came up with a plan like this, it was all full of circles and we have the service I guess more towards the perimeter. There were two dance floors, and again for the first time here, it is clear that he gave a prominent position to the DJ which is this place here, and this is the machinery to amplify the music. So, this is how the interior looked like, it was full of these stalactites also, there was something with the stalactites, everyone liked it, and the lights were also coming from these elements in the ceiling. This is the interior of the club, it was a bit more busy, we will go onto other pictures later, this is for me one of the crucial drawings which I found in my investigation because it is the first time I saw an architect draw a DJ playing in the DJ booth.

So, this is the DJ booth and there you have the section and the elevation where the DJ could control everything. The funny thing is that obviously he was not calling him DJ, the word didn't exist at that moment, so it was like the control deck of lights and sound. There was an understanding that there was a director of the architecture, and there was a director who would control the atmosphere of the space. A little bit like Cedric Price Fun Palace, like there is a machinery and someone behind it that can activate and deactivate the atmospheric parameters so people can have fun during the night there. This is the appearance of the DJ booth, at that time they were using both vinyl and magnetic tapes, actually the first steps into DJing was through magnetic tapes, not through vinyl, but at that moment they had already introduced vinyl; and there were some, their names are not well known but there were some famous DJs of this place that were there for years. But that was not the only thing, obviously at that time they did not yet have commercially produced lighting devices so what they had to do was to design all these devices as Bruno Munari was doing.

These are some of the devices they designed for this club, they had different applications, there is many more, they were doing it in collaboration with a light designer company that was external to the core group of designers from there, and what they managed to get was something like that, this ceiling that was full of lights and effects. And obviously in these kind of pictures it’s difficult to capture, but one of the owners, when he’s explaining about the experience of that space he’s talking about this white box that is pulsating, and actually that transports you to a certain idea of cinema. They were often making a relationship between the experience of these interiors with cinema, and most of the newspapers were making the relationship with a certain idea of psychotropic experiences. This is another image of the interior, completely full of people. These are some of the examples of Platja d’Aro, obviously there are more, it was said that in one normal night there could be about 20’000 people having fun in the discotheques of Platja d’Aro, so it was not a small phenomenon, there were many of these clubs for a lot of people to gather together. These are some of the images that I really like that are trying to capture a little bit more of what is actually the interaction of the lights with the bodies, the movements and the position of the bodies in different points.

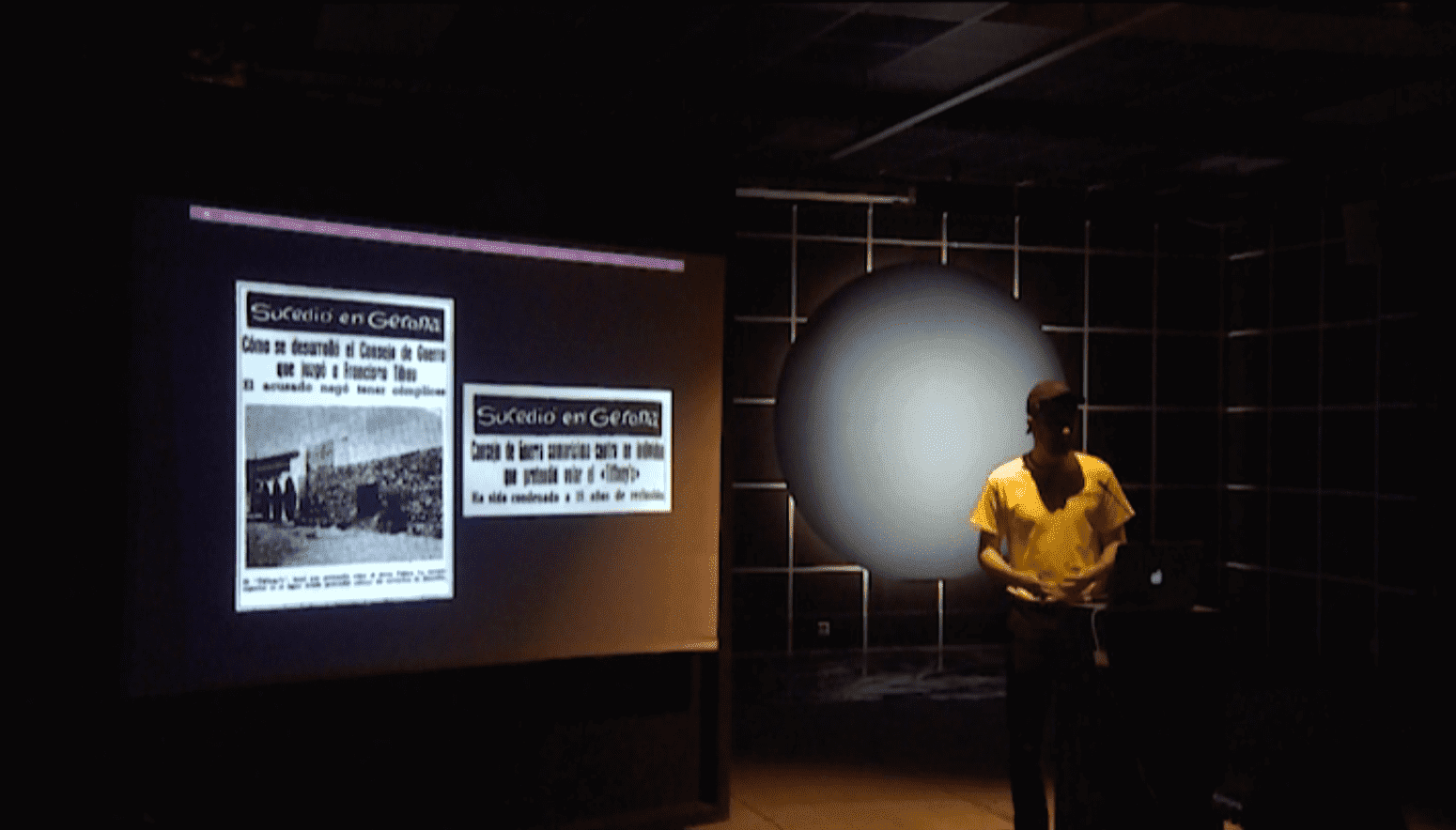

One of the arguments that Roland Barthes makes when he’s talking about the discotheque in Paris, that is actually ten years later than this, is that what is the most interesting aspect in relationship to visual relationships, or the visual regime within those spaces, is that while in the theatre there is a public and there is a protagonist, here obviously everything is twisted around and everyone becomes both public and protagonist, and you are immersed in this crossed regime of views. At the same time the bodies are interrupted by the flashing lights and this provokes a completely different reading of the performativity of the body. These are two other pictures of the, I think it’s 71’ here, Regàs, it was one of the directors of that space, one of the artistic directors that was very much related with the Gauche Divine, which was the intellectual bourgeoisie of the time in Catalunya that was also related with the school of Barcelona of cinema, a quite overlooked experimental group of cineastes from that time. Lately they’re having some studies of this experimental school of cinema from Barcelona in relationship to post deconstructivism theories and Deleuzes understanding of cinema etc. There is very clear relationship to these experiences of the discotheque as a non-place, because you are completely disconnected from the exterior, and spaces obviously that work through lighting to reconstruct a certain narrative of time, something that you completely lose track of there. We talked a lot about light, and we talked a lot about sound, but drugs were also very important in Spain. During Franco times, Spain was not part of many international treaties for drugs, that meant you could go to the pharmacy and basically buy amphetamines for free. It was known that Spain was kind of the pharmacy of Europe, that you could go there because it was a free drugstore for everyone, since you didn’t need any prescription. These are only some of the brands that you could directly buy in the normal drugstore. So, all these clubs were fueled by the consumption of these drugs, that were at the time completely legal drugs, that would be consumed by both the club goer and the housewife the same, so it was nothing particular of the club. Here we come to, it’s almost the conclusion, a final point, the last club I showed opened in 77’-78’, and in 79’ there was a group of activists, of communists, anarchists, it was not so clear because they were very young and didn’t even know what they were looking for, but what they knew is that they were fighting against the Franco regime, they were fighting against the dictatorship and they understood that tourism had a direct link with the dictatorship, that tourism was actually economically fueling the dictatorship. Actually, there was also lots of criticism from intellectuals from Catalunya, like Josep Pla, who was one of the most important writers and commentators of the time, he was saying that in the regime of Franco all industries are controlled, you cannot do anything under the control of the regime, except tourism, you can build whatever you want, you can do whatever you want in the coast, no one will control you because they were leaving this room actually for the business to proliferate let’s say, and keep the country in place. This group of people decided they wanted to put a bomb in a discotheque, so one of them stole some dynamite from somewhere and went into Tiffany’s, not the last one, the previous one, and he put the bomb there. They caught him when he was trying to escape after putting the bomb, the discotheque was full of people, so the bomb didn’t explode, but he was actually arrested so this case was one of the, I don’t know exactly in English, I think it’s a court martial, un “concilio de guerra”. There have been only two during Franco times, and this was one of them, and they decided that this was a terror attack against the nation and these guys were tried and went to prison for many many years. So let me come to my conclusion and put forward a bit my ideas behind that, at the beginning I think I was quite naive when I was doing all this investigation and thinking that the discotheque was always this kind of apparatus, that it was a kind of device that was acting as a counterpart to this mechanization. There was an advanced technological device that could liberate the body, that could liberate the post-industrial body, and give back a certain freedom of speech; and when I say speech I don’t mean speaking with words but actually speaking through performativity, through gesture. But suddenly when I started looking more in depth at the emergence of discotheques in the coast, I realized that there was another aspect to all of that, that is this aspect Lefebvre talks about, Henri Lefebvre who is this French thinker, funnily enough, one of the pictures that comes in his book which is a manuscript towards an architecture of enjoyment 5

, that basically analyses what he calls neo-colonization of the Mediterranean coast through the industry of tourism, and there is a picture of Lefebvre in Sitges, the place where the first Pacha started. So all his theories that were elaborated with Mario Gavila, who is also another sociologist from Spain, they were both working together in France, analyzing what was the impact of this colonization of spaces, and I find extremely interesting because while on the one hand I really believe there is a component in the discotheque that aligns with these ideas, there is another theoretician, who is Douglas Crimp, who was taking some notes about his experience in going out in nightclubs in New York in the seventies. And he was saying, I’m not going to read it because it’s quite long, but basically he was saying, how long will it be to make a machine that can produce ecstasy and pleasure artificially, I think it was a rhetorical question, obviously the discotheque can produce this physical pleasure, scientifically it has been demonstrated through the alpha waves. But I think what you have in there, he says, is a very primitive pleasure, this kind of jouissance. It was at least, at the very beginning in Spain, because it can change its categories and values depending on its geographical place and time, at that moment it was also a way of making of a space another element for consumption. And one the aspects that interests me quite a lot as well is the mercantilization of those spaces, all these night clubs had actual merchandise, it’s the first time that space gets merchandising. So, you have t-shirts, you have flyers, you have booklets, you have records, you have absolutely everything and you have shops. So what they are selling is an experience, it’s a special experience, so in the sense of Lefebvre, if we interpret it from a more radical point of view, obviously what was created there through the money of tourism; the capacity of technology

was the illusion of the liberation of the body, but at the very same time putting forward a new form of consuming space in contemporary terms.

Pol Esteve Castellò is an architect and co-founder of the architectural firm GOIG and a graduate of the Barcelona School of Architecture and the Association School of Architecture in London, where he completed a Master’s degree in History and Critical Thinking in Architecture. He has collaborated with the Museum of Contemporary Art of Barcelona (MACBA), Olga Subiròs Studio, Cloud9 Architects in Barcelona and R&Sie(n) in Paris. He has designed projects for institutions such as DOCUMENTA, Venice Biennale and CCCB. His work focuses on the influence of electronic and chemical technologies and so-called non-standard bodies on the production of space, which has led him to become interested in backrooms, discotheques and nightclubs, artificial light, drugs, emission devices and applications.

- Escola Tecnica Superior d'Arquitectura de Barcelona (ETSAB) belonging to Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya (UPC). ↩

- Roland Barthes, "At Le Palace Tonight", Vogue Hommes, no. 10, May 1, 1978. ↩

- Siegfried Giedion, Mechanization takes command, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1948). ↩

- Pachá, el arquitecto de la noche, directed by Miguel Bardem (Spain: EndemolShine Iberia, 2015). ↩

- Henri Lefebvre, Toward an Architecture of Enjoyment, ed. Lukasz Stanek (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014). ↩