Javier Fernández Contreras

"El Croquis Night. Excursus into Nocturnal Obliteration in Architectural Media." Interiority, Vol. 4, No. 2 (July 2021): 181-190

"El Croquis. Une édition nocturne." Plan Libre, No. 179 (December 2020): 12-14

"Taking pictures at night is very difficult because you only have about 20 minutes; the sun is going down. There's a moment when it's perfect, then it becomes less perfect, and finally, you can't do it because it's too dark. You need to see the outline of the building,"1

Richard Levene, co-founder of El Croquis

For centuries, architectural theory, discourse, and agency have been based on daylight and solar paradigms. References to the night in Vitruvius’ De architectura (30-15 BC), widely considered the founding text of Western architectural theory, are residual, and similarly, they are scarce in the most influential Renaissance treatises, such as Leon Battista Alberti’s De re aedificatoria (1452) and Andrea Palladio’s I quattro libri dell’architettura (1570). Likewise, the seminal writings on modern architectural theory rarely refer to the nighttime urban architecture environment, which can be evaluated both textually and photographically. Philip Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock’s The International Style (1932), the book resulting from the MoMA exhibition that introduced modern architecture to America, illustrates a clear preference for daytime pictures,2 noting that “the photographs and the plans were for the most part provided by the architects themselves.” 3 This diurnal rationale is further discernible in the books that would establish the intellectual framework of architectural modernity, i.e., Nikolaus Pevsner’s Pioneers of the Modern Movement (1936) and Sigfried Giedion’s Space, Time and Architecture (1941), where less than 5% of the images are purely nocturnal, understanding the term in the circadian acceptation of absence of daylight. In all cases, accompanying texts rarely refer to night spaces, not to mention nighttime activities or associated behaviors.

In the second half of the 20th century, authors such as Reyner Banham, Venturi and Scott Brown, and Rem Koolhaas corrected to a certain extent the invisibility of the night in architectural theory with influential books such as The Architecture of the Well-Tempered Environment (1969), Learning from Las Vegas (1972), and Delirious New York (1978), which address the performance of night architecture and the spatial types present in the construction of modern domesticity and leisure culture in Western societies. These texts emphasize how the role played by the night in the construction of contemporary cities and societies has been central in the transformation of the urban environment since the invention of artificial light in the 19th century, forever disrupting the means of material and cultural production.

From casinos to nightclubs, movie theaters to corner shops, the identity of human beings and their associated domestic, professional, and cultural spaces are inseparable from the night. However, presently, most influential specialized journals continue to construct an architectural representation where images and texts are recurrently day-based. Important history books published in the last 50 years, such as Leonardo Benevolo’s Storia dell'architettura moderna (1960) and Kenneth Frampton’s Modern Architecture: A Critical History (1980), have likewise institutionalized this diurnal episteme.

" Presently, most influential specialized journals continue to construct an architectural representation where images and texts are recurrently day-based. "

El Croquis is one of the most prestigious architectural magazines in the world. Founded in 1982 by Richard Levene and Fernando M. Cecilia, it publishes five monographs on influential architects every year. Through a series of recurrent features such as the preference for frontality, the display of mirroring photos of interior spaces, plans displaying characteristic linearism, construction details paired with façade photos, and the objecthood and exteriority of architecture models, El Croquis has shaped architectural history over the last 40 years. The volumes dedicated to established Pritzker Prize names like OMA Rem Koolhaas, SANAA Sejima & Nishizawa, Herzog & de Meuron, or Alvaro Siza are considered these architects’ respective oeuvre complète. As opposed to other architecture journals, its editorial line, photography, and layout are the direct result of the decision making of its two editors, who curate everything from the architects featured in the journal to the frame and viewpoint of every single photograph. This creates a unique sense of continuity in El Croquis, both unexpected and uncanny, where architectures as diverse in their idea and spatiality as those of Rem Koolhaas, Enric Miralles, SANAA, Zaha Hadid, or Frank Gehry become Croquis-like when they are published in the journal.

The entanglements between the editors’ vision, habits, and the mediation of architecture are inseparable. Initially, Levene and Cecilia were simply two architecture students confronted with the challenge of delivering their final degree project at the Madrid School of Architecture (ETSAM) in the early 1980s, and the first issues of El Croquis were thus a miscellaneous collection of final projects of young graduates, full of construction details that fellow students could use as reference. It was not until issue No. 15, entirely dedicated to the projects of Manuel and Ignacio de las Casas, two lecturers at the same school, with an addendum on student projects, that the monograph format was devised. Further monographs on Rafael Moneo (20), Estudio PER (23), and Viaplana-Piñón (28), introduced by a critical essay and an interview with the architects, would progressively confirm the now well-known format of the journal. The transition from student projects to professional agencies did not mean a total reshaping of the journal. Original elements such as the abundance of construction details, plans printed in large size, and unbuilt projects presented mainly through models remained, yet photography, as medium and episteme, gained unprecedented centrality.

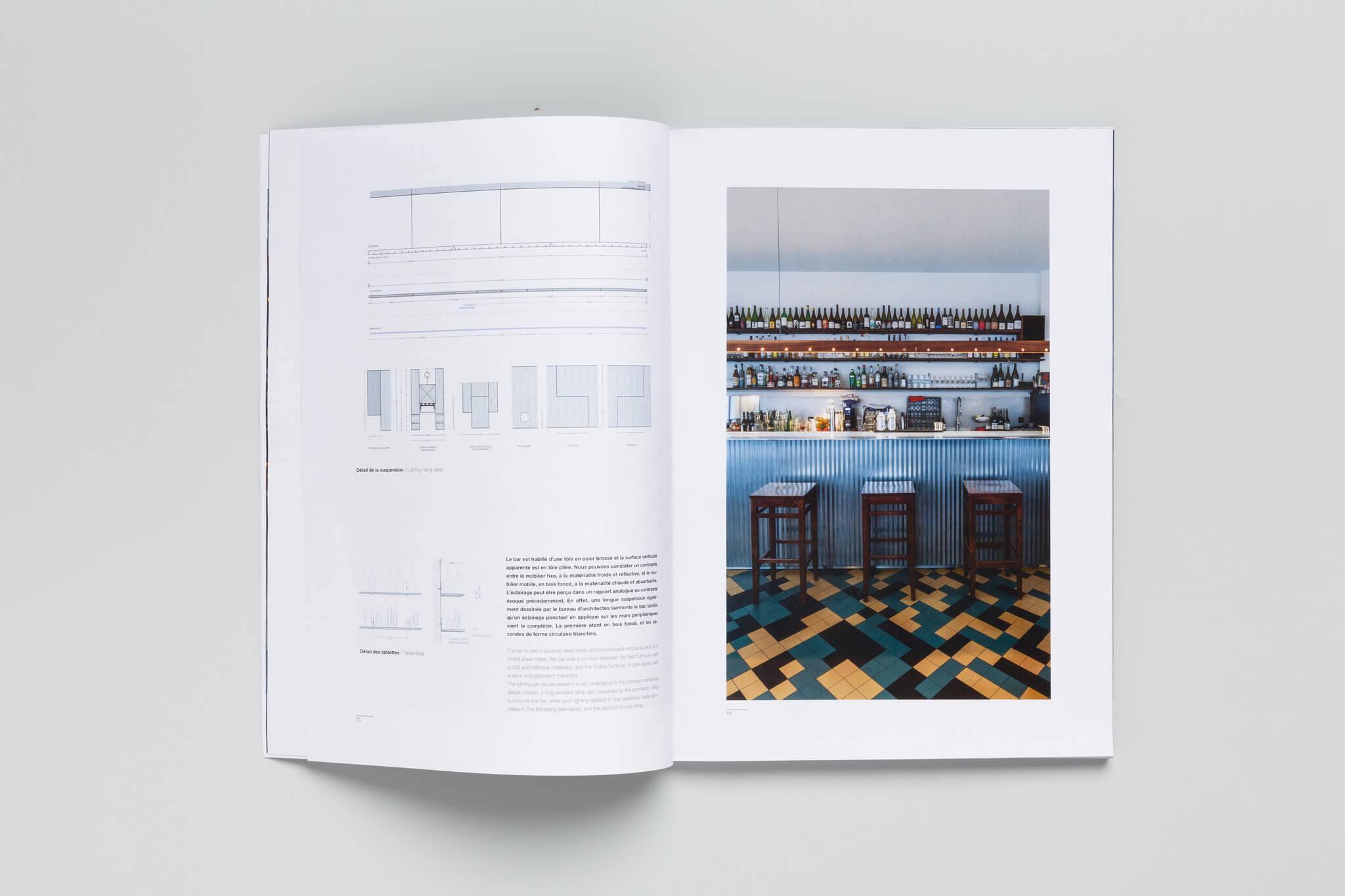

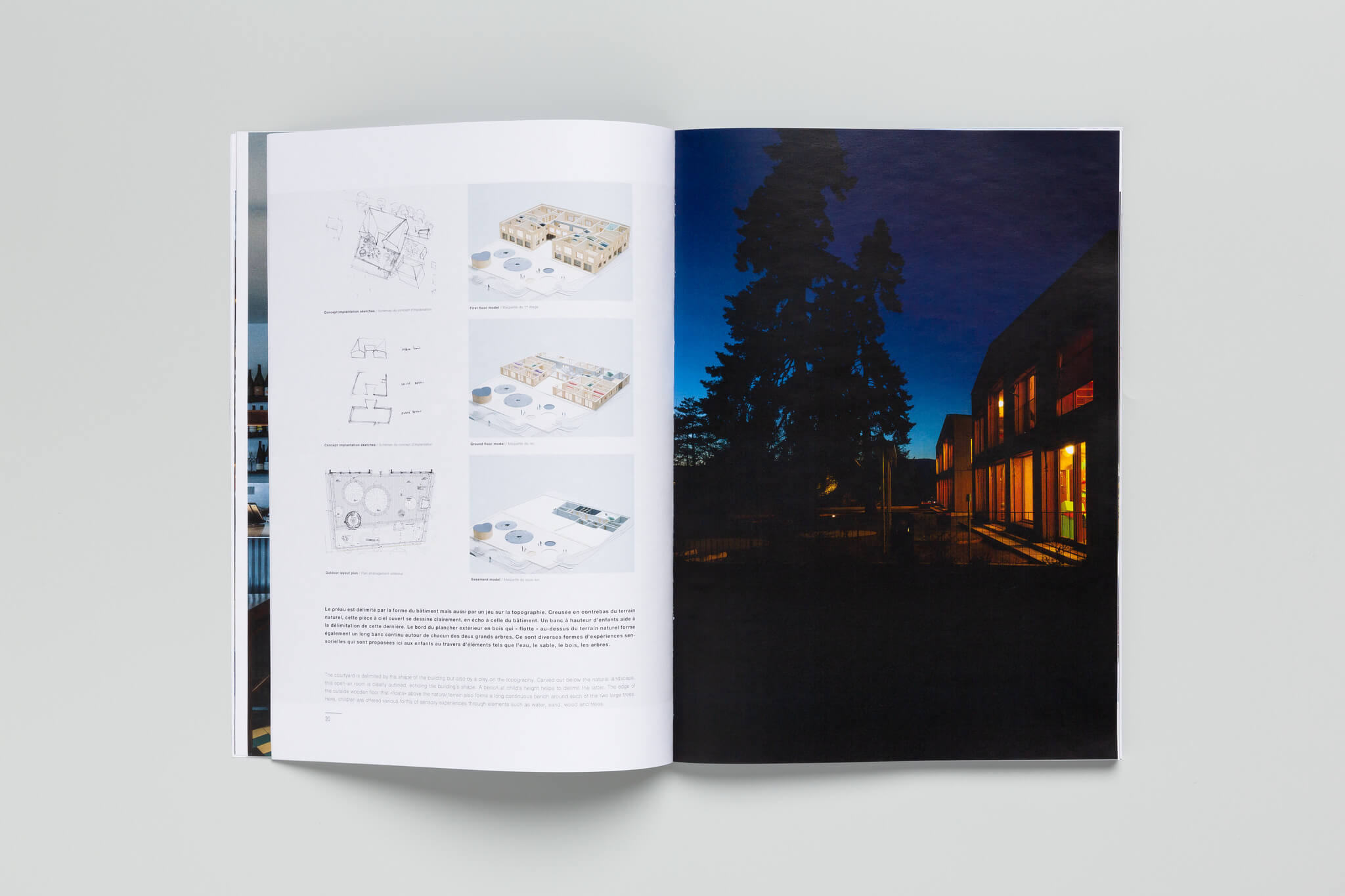

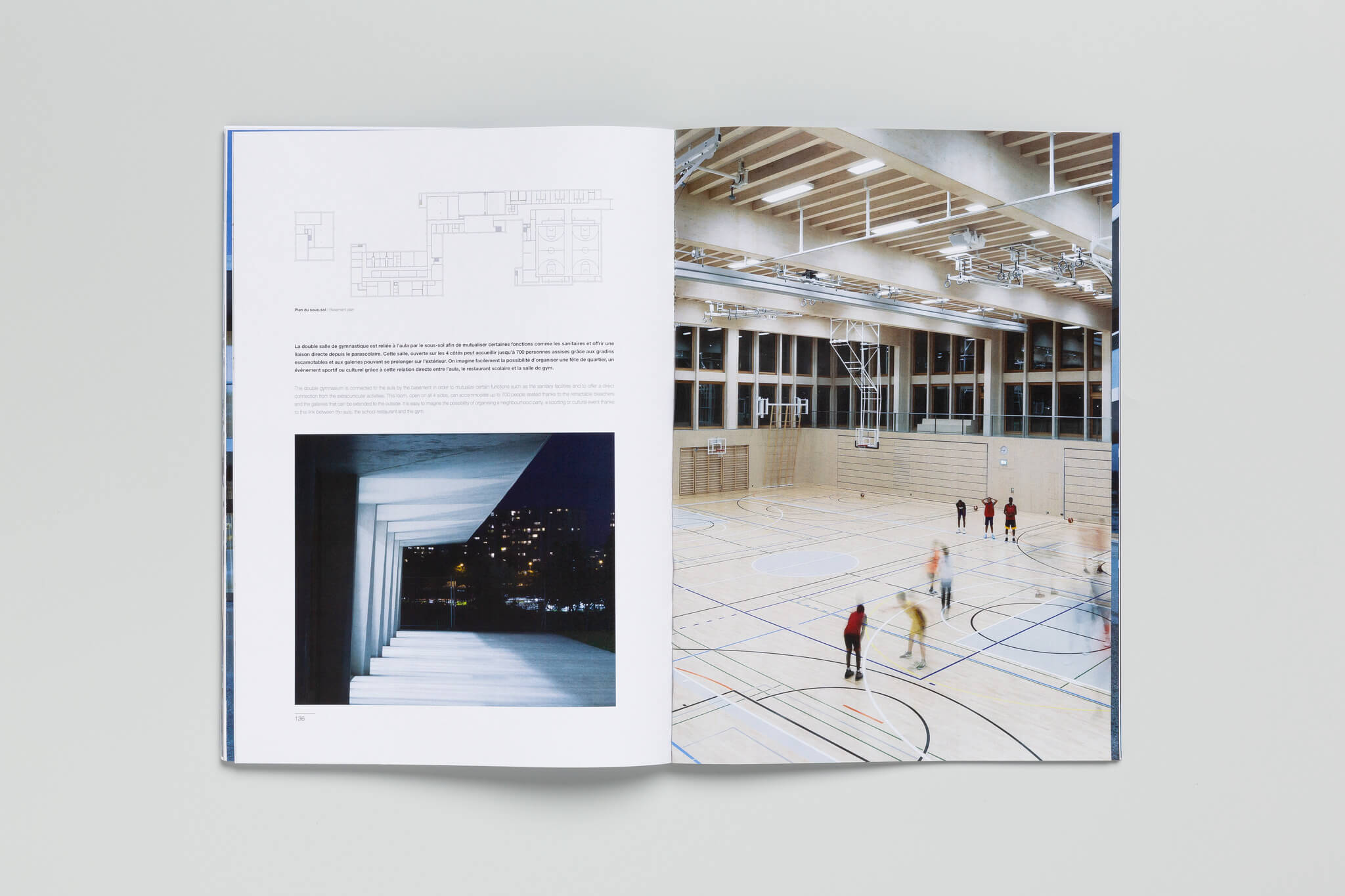

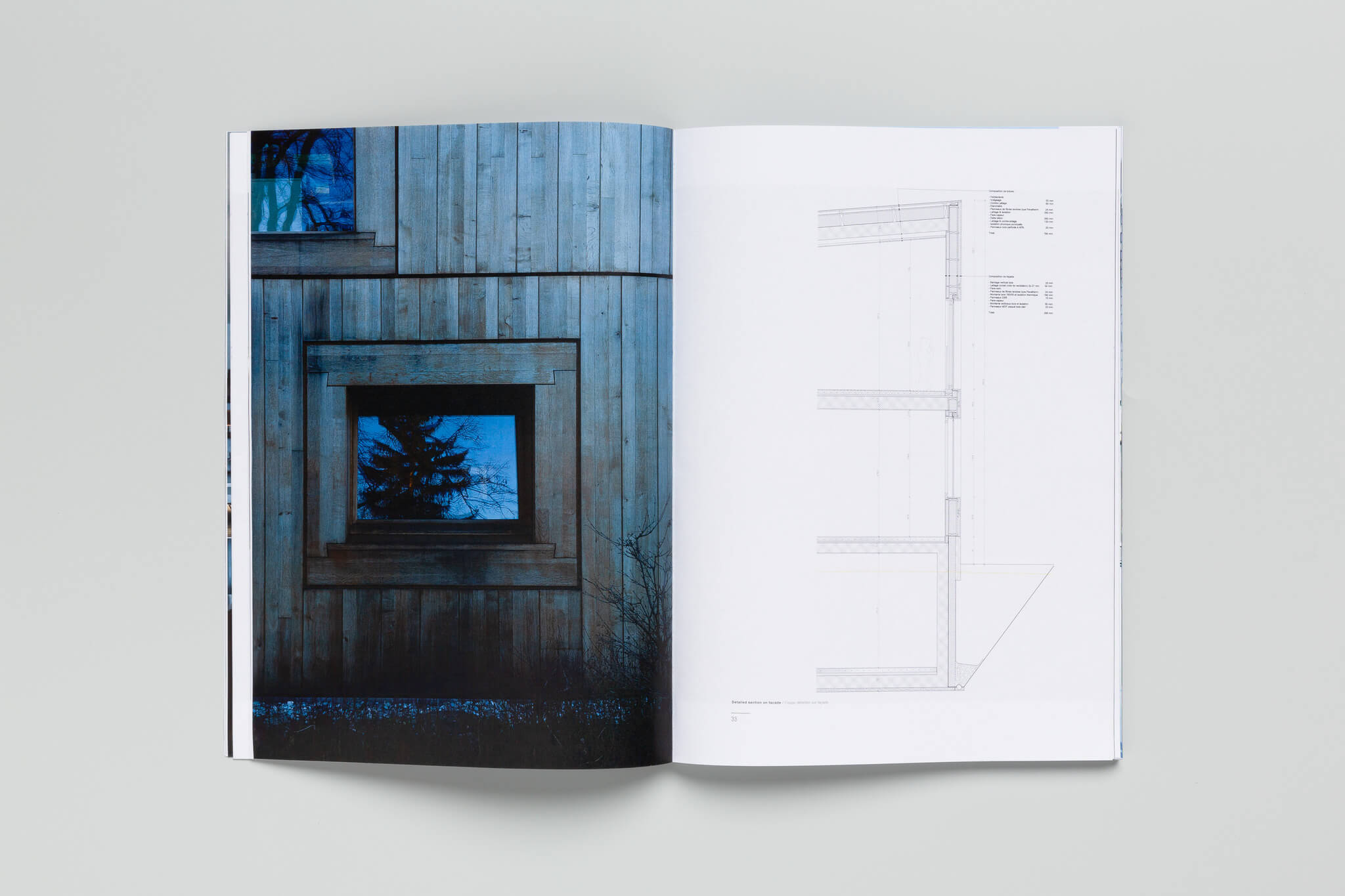

The journal almost never publishes night photography. During a workshop in February 2020, HEAD – Genève invited Richard Levene to create a “night edition” of El Croquis. The workshop focused on the idea that the night is a forgotten paradigm in the construction of contemporary architectural discourse. Students developed an El Croquis Night issue based on the magazine’s photographic and editorial language, spending two weeks photographing prominent contemporary buildings in Geneva under Levene’s supervision from the blue hour in the evening to after nightfall, a material that they later laid out and edited in a virtual edition of the journal. The combination of photographic portrayal, plans, text selection, and editing of the collected material enabled students to understand El Croquis’ working methods. The workshop was both an invitation and a critique. By keeping the format and methodology but reversing the circadian rhythm, a mirror effect was achieved, opening up the following question for architectural media: Is architectural representation diurnal by default?

"The night is a forgotten paradigm in the construction of contemporary architectural discourse."

In the case of El Croquis, take the figure of a journey. Most buildings published in the journal have been visited directly by Levene and Cecilia with their photographer, Hisao Suzuki, who joined the journal in 1988. For monographs involving projects in different countries, this implies careful travel planning, in coordination with the architects and the buildings’ users. Building visits are scheduled during the day, with a maximum of three per day, arranged with the architects and the property. This program is rarely altered, never mind whether it is the blue hour or sunshine, regardless of weather conditions or season. For instance, all buildings in the monograph on José María Sánchez García (189) were photographed over three straight sunny days in Extremadura (Spain), whereas those in one of the monographs on SANAA Sejima & Nishizawa (139) show varying weather conditions in different Japanese, European, and American locations. The point of view, carefully chosen, discussed, and agreed by Levene and Cecilia, is executed, not chosen, by the photographer. In the genealogical tree of media, Suzuki would belong in the category of automaton, his principal role being in the execution and processing of photography, not its conception. Pictures from other photographers are included only in exceptional cases, such as difficulties accessing particular points of view, temporary closures, or building deterioration.

Night is reserved for dining, in many cases with the architects, and friendly discussions around bottles of wine, where the names of other architects might come up: “Have you seen the work of this architect? Who is the next big name in Japan?” Following the normal circadian rhythm in this way, however, is unrelated to architectural rhythm. Take Rem Koolhaas for instance. The Seattle Library is mostly used during the daytime, and the El Croquis photographs thus reflect the life of the building in monograph No. 134/135, whereas the Casa da Musica in Porto, mainly an evening building in terms of programming, appears empty, human-less in the same issue. In 2006, Koolhaas introduced the idea of “post-occupancy,” originally a term reserved for the evaluation of buildings involving user feedback,4 to architectural criticism in a special issue of the journal Domus by looking at four OMA public buildings (including the Casa da Musica and the Seattle Library) through the broader media and cultural context within which they operate, empowering the critical experience of users.5 The issue included abundant nighttime material on the projects portrayed. Long before the social media era, it was key in the articulation—or consolidation—of a radical shift in the point of view through which architecture is regarded, portrayed, and circulated, from the eye of the specialist to that of society at large, giving it new agency in architectural discourse.

The resistance to night photography in El Croquis, other than due to habits and trip schedules, is related to the blurring of architectural volumes at night. Atmospheric, diffuse, or blurred would never describe any of its photography. There is a diurnal exteriority in this way of thinking – “Because you need to see the outline of the building,”6 as Levene would claim in a conversation on the history of the journal. Only one night photograph, that of the Rolex Center in Lausanne by SANAA, has made the cover of El Croquis (155). This creates, literally, an image that shapes the rest of the content. There is a recurrent absence of lighting plans, not to mention diagrams, in the drawings. The non-visuality of architecture, i.e., its acoustic, thermal, and lighting qualities, is recurrently rendered invisible, not only by the limitations of photography but also in the choice of the accompanying graphic material.

Through photography, El Croquis objectifies – in the literal sense of rendering objects – architectural spaces, particularly from the outside, with a recurrent yet not exclusive preference for the isolated building, be it the small villa or the large public building, surrounded by trees or urban elements, yet bucolic, meteoric in its presence. It is no wonder that architecture models are almost always portrayed from the outside, through a bird’s eye view, as objects, becoming as Levene claims, “pieces of jewelry.”7 Models are hardly ever portrayed from the inside, and when they are, space is the negative of tectonic elements, floors, walls, columns. This keeps alive the modern dissociation between architecture and the applied arts, prioritizing the empty, human-less, isolated object over the assemblage.

Most buildings published in El Croquis are houses or public buildings. Visits are arranged with the architects and the property. In the case of the houses, owners are invited to leave when their interiors are portrayed. Then, Levene and Cecilia perform an instant mise-en-scène: ugly objects of everyday life are removed, hidden. If, in Le Corbusier’s photography, objects construct the fiction that someone was there just before the shoot, in El Croquis this presence is recurrently obliterated, rendered invisible. There are no human beings in most pictures. Sometimes Levene and Cecilia pose, in Hitchcock cameo style, as passers-by, but never as users. In sports courts they are never playing sports, in libraries never reading books, as if underlining the artifice of the operation. On the published architects’ side, plans are redrawn, models remade (or simply made), projects invented (“for a private customer”), buildings “cleaned,” garbage bins removed, signs temporarily removed, objects of everyday life erased, people invited to leave. If “post-occupancy”was the promise that buildings were to be launched into society and observed through the process of their appropriation by human beings, then El Croquis holds the promise of an architecture never to be occupied or inhabited, where spaces remain pristine, eternally diurnal.

Download Full Essay in French

Download Portfolio

Download El Croquis Night

Photography: © Michel Giesbrecht, HEAD – Genève

- Richard Levene, “El Croquis, Night Conversation” interview by Javier F. Contreras and Sven Högger, February 21, 2020, https://issue-journal.ch/flux-posts/el-croquis-a-conversation-with-richard-levene/. ↩

- Only 4 images out of 83 photographs show artificially-lit spaces: Alvar Aalto’s Turum Sanomat building, Uno Ahren’s Flamman Soundfilm Theater, Marcel Breuer’s Berlin apartment, and Jan Ruhtenberg’s living room in Germany. See: Henry-Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson, The International Style (New York – London: W. W. Norton & Company, 1932/1995). ↩

- Henry-Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson, The International Style (New York – London: W. W. Norton & Company, 1932/1995), 9. ↩

- See: Wolfgang F. E. Preiser, Edward White, and Harvey Rabinowitz, Post-Occupancy Evaluation (Routledge Revivals) (London: Routledge, 2015). ↩

- See: Post-Occupancy, ed. AMO / Rem Koolhaas (Milan: Domus d’Autore, 2006). ↩

- Levene, “El Croquis, Night Conversation.” ↩

- Levene, “El Croquis, Night Conversation.” ↩